In the first installment of this series, John Hladun was introduced as a member of the left-wing Cooperative Commonwealth Federation in Winnipeg, Manitoba. A CCF candidate in Winnipeg’s 1943 and 1944 municipal elections, Hladun departed the CCF some time in 1945 in circumstances that remain unclear. Two years later, he resurfaced in Toronto as a fervent anti-Communist writer, public speaker and political agitator.

In October and November 1947, Hladun established his anti-Communist bona fides in a serialized political biography published in the popular Macleans’ Magazine. The three-part series, “They Taught Me Treason”, was a sensational account of Hladun’s time in the Communist Party of Canada in the late 1920s and early 1930s, including his nine months in the Soviet Union in 1930-1931.1

The following account pieces together Hladun’s story using They Taught Me Treason, English-language newspaper records, scholarly publications, and several dissertations. During the course of the research for this article, I learned of Hladun’s obscure autobiography published in Ukrainian in 1990 under the name “Ivan Hladun.”2 I can’t read Ukrainian and I don’t have local access to the book, so there is some marshalling of resources required for travel and translation. For now, I will continue to sketch out the story of John Hladun using the aforementioned sources. Footnoting will be used where the source is not Hladun’s Macleans’ Magazine.

From rural village to Winnipeg

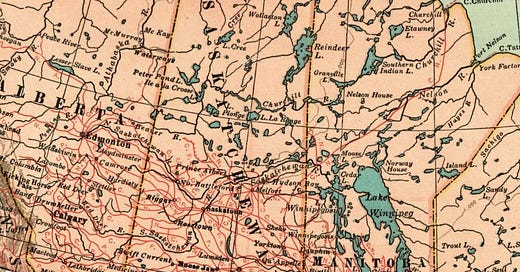

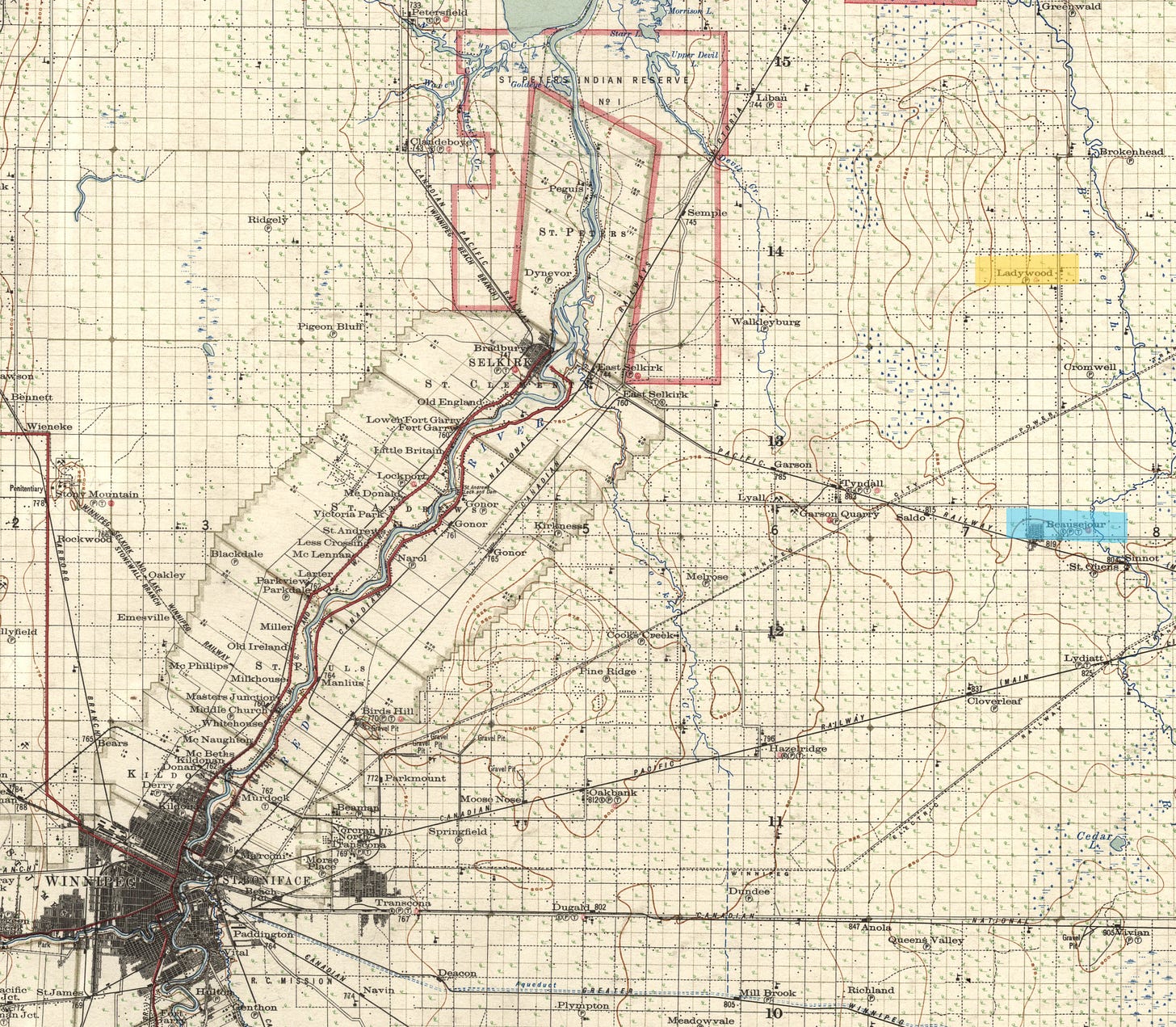

Depending on the source, John Hladun was born in 1901 or 1904. Macleans’ Magazine and the Ivan Hladun fonds at the National Archives of Canada say 1904, but his 1991 obituary says November 4, 1901.3 We do know Hladun was born in the agricultural district of Brokenhead, Manitoba in the small village of Ladywood some 70 kilometres northeast of Winnipeg. Brokenhead’s population had not yet surpassed two thousand people in 1901. The region’s farm lands are a short distance from the western edge of the Canadian Shield where the prairies begin and span westward to the Rocky Mountains.

John Hladun’s father, Pantaleone “Panko” Hladun, reportedly immigrated to Canada in 1896 from Bukovyna, a region of western Ukraine within the Habsburg (Austro-Hungarian) Empire and bordering Romania. In Manitoba, Panko Hladun married Annie Struss on November 22, 1898 in a ceremony officiated by Reverend Father Cherrier.4 Panko and Annie’s first child was John. The family in Ladywood, including his grandparents, were “devout Greek Catholic”. Religion, explained Hladun, “was not a duty but a glorious benefice.” Panko Hladun died in 1914, leaving behind Annie, John, and three younger school-age siblings.

As a child, Hladun spent time in school, farmed and cut cordwood. “When I had cut enough wood for a load I would haul it with our team of oxen to Beauséjour – 12 miles each way – sell it at two dollars a cord and use the money to buy groceries. To make this trip I would get up at four o’clock in the morning. I’d return late at night.”

Hladun describes his first encounter with left-wing politics as a visit to his school by members of the Ukrainian Labor-Farmer Temple Association. Hladun, already an avid reader at a young age, became a subscriber to Ukraïnski robitnychi visty (Ukrainian Labour News). The Ukrainian-language paper was edited at various times by several prominent ULFTA figures, including Danylo Lobai, Myroslav Irchan and Matthew Shatulsky. All were members of the Communist Party of Canada, which was formed in 1921. This is relevant because ULFTA was not in fact formed until 1924, well after Hladun was attending school in Ladywood.

Whether he was born in 1901 or 1904, Hladun would have in fact encountered ULFTA’s predecessor organization, the Ukrainian Labour Temple Association. This organization, ULTA, was formed in 1918, and began publishing Ukrainian Labour News in 1919, the same year it completed its famous labour temple in Winnipeg.

Hladun described a personal struggle between his religious upbringing and the denouncements of capitalism in the newspaper. Hladun also recalls his mother scolding him for being a “Muscovite”, and explaining how they left their homes in Ukraine “because of enslavement by the Muscovite and the Pole.” Such views were not uncommon among Ukrainians who were subjects of the Habsburg and Tsarist empires in the 1890s. Poles were also seen as rivals in what is now western Ukraine. For example, the region’s biggest centre, Lviv, was majority Polish and remained so until the Second World War.

It is very likely events in Europe were the source of Hladun’s attraction to the left. These were the years in which popular revolutions toppled the Tsar, the Habsburgs and the Kaiser, and brought a close to the “Great War” bloodbath unleashed by Europe’s empires. In these few years, a new Europe, and a new Ukraine, seemed possible. Hladun would have also been aware of the Winnipeg General Strike in May-June 1919 but makes no mention of it.

It was in this fervour that, at the age of eighteen, Hladun moved to Winnipeg and became active at the new Ukrainian Labour Temple at the corner of Pritchard and McGregor in the city’s North End: “I threw myself wholeheartedly into the activities of the youth section, wrote articles for the magazine, took part in debates at the Temple and general strove to earn myself a reputation for zeal and reliability.”

Although Hladun’s 1947 account disparaged ULTA/ULFTA as “cockeyed” leftists who wanted to impose “Bolshevism” on Canada, historian Rhonda Hinther’s research on these organizations demonstrates a much more complicated relationship between ULFTA, with its broadly popular cultural and educational programming, and its political perspectives linked to the Communist Party of Canada. ULFTA’s autonomy was in fact a grievance among several Communist leaders in Canada.5 This relationship between ULFTA and the Communist Party would become central to Hladun’s life in the 1930s, and forms part of the next installment of this series.

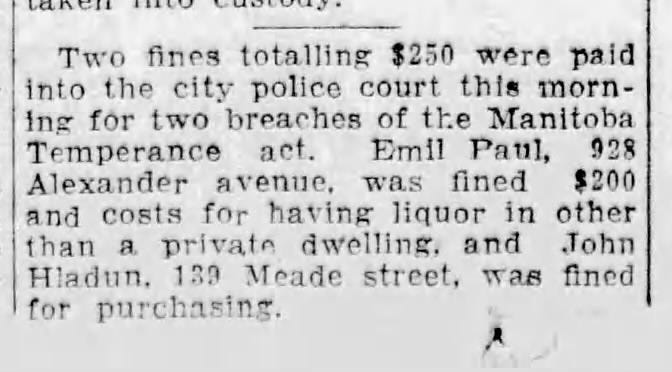

The earliest English-language newspaper reference to Hladun in Winnipeg is from 1925. There is a small report of Hladun’s arrest for violating the Manitoba Temperance Act. Hladun was fined a hefty $50 ($885 Canadian dollars in 2025) for illegally purchasing alcohol. Emil Paul, the seller, was also arrested and fined $200 ($3,543 Canadian dollars in 2025). Hladun’s Macleans’ Magazine story makes no mention of this encounter with the law, but it is clear he did not go down the same path as Emil Paul. A few years later, in 1930, Paul was arrested in a big bust of a prolific gang of robbers. Paul’s thefts were of gasoline and shoes, while the major culprits were jailed and lashed for violent robberies involving thousands of dollars.

In the 1925 newspaper report of Hladun’s arrest, his home address is listed as 139 Meade Street, a two-story house near Main Street on the edge of the working-class neighbourhood of Point Douglas. The house appears to have been owned by John Olensky, the husband of John’s younger sister, Mary.

Agitation in Kenora and Lethbridge

Hladun’s involvement with ULFTA led to his recruitment to the Young Communist League and appointment to its “Agit-Prop” committee, which involved writing articles for the League’s newspaper and talking with young workers in Winnipeg. He also took part in a six-month political education program held at the Labour Temple and taught by several veteran socialists, including Dr. J. Karach, then editor of the Ukrainian Labour News. Once he completed his training, Hladun became a full-fledged member of the Communist Party in 1928.

Hladun claimed his first assignment was to “take charge” of the ULFTA branch in Kenora, Ontario and use it as cover “to form a cell of the Communist Party.” Hladun says he made little progress with devout Ukrainians in Kenora, but was “able to stir up a certain amount of dissatisfaction” among railway and paper mill workers. Having recruited ten members and developed a plan to capture the leadership of the local paper mill union, Hladun says he was moved back to Winnipeg. Kenora, he claims, was a test in which he had exceeded Party expectations.

After Kenora, Hladun was sent to Lethbridge, Alberta in early 1930 as part of the Communist Party’s renewed efforts to organize coal miners. The Communist Party’s presence in Alberta was not insignificant as the party had a foothold in the Mine Workers’ Union of Canada (MWUC) which was affiliated to the All-Canadian Congress of Labor (ACCL). The MWUC was built by miners across the political spectrum who had rebelled against the United Mine Workers of America’s District 18 in Western Canada.6

As for the ACCL, it was established in 1927 as an independent Canadian rival to the powerful Trades and Labor Congress which was comprised mainly of international craft unions headquartered in the United States. The ACCL’s backbone was the Canadian Brotherhood of Railway Employees led by Aaron Mosher, a social-democrat who had clashed with the TLC over craft union claims to jurisdiction in Canada, leading to the CBRE’s exclusion from the TLC.7

The Communist Party of Canada was initially enthusiastic about the formation of the ACCL but this perspective soon changed with the new “Third Period” strategy and directives emerging from the 1928 Congress of the Communist International in Moscow. Premised on the expectation of capitalist economic crisis and renewed class struggle on an international scale, the new strategy entailed breaking the MWUC from the ACCL and affiliating MWUC to the Communist Party’s new labour central, the Workers’ Unity League. This effort largely succeeded but it was a move that resulted in Aaron Mosher becoming a powerful life-long enemy of Canadian Communists, although that is a story for another time.

This is the background to Hladun’s arrival in Lethbridge, home to Alberta’s largest MWUC local of about six hundred miners. Hladun says he was installed as secretary of the local party which comprised only 24 members, of whom four were miners. Soon after his arrival, a “crack labor organizer”, in Hladun’s words, Harvey Murphy, also arrived in Lethbridge.

Murphy had come from British Columbia where he was organizing with the International Union of Mine, Mill and Smelter Workers. Of Jewish-Polish heritage, he was born in 1901 in Berlin, Ontario (renamed Kitchener in 1916), and had anglicized his name. Murphy had encountered the revolutionary syndicalism of the One Big Union in Canada’s 1919 labour revolt and established himself as a young, capable, militant labour organizer in different parts of the country. According to Seager, Murphy would become “perhaps the most influential communist in the Canadian trade-union movement in the 1940s.”8

Organizing the unemployed

Under Murphy’s auspices, Hladun and the Communists in Lethbridge began their work. Murphy focused on organizing the miners and launched the Lethbridge-based Western Miner under his supervision. Hladun’s focus was among the growing ranks of unemployed, which had become a priority for the Canadian Communists after the 1929 stock market crash. Hladun gained a local profile, as reported in the Lethbridge Herald, for leading two “hunger marches.”

The first march started with a mass meeting on April 3 in Galt Gardens. About 350 people attended. Speeches were delivered in English, Hungarian and presumably Ukrainian. With Hladun as the chair, an unemployed committee of twelve men was appointed to take a list of six demands to City Hall. The demands were:

That the unemployed be given full maintenance ($1 per day for single persons and $2 per day for married) immediately.

That the unemployed be given the work at trade union rates.

That there will be no relief work imposed as a compensation for the maintenance.

All the work that will be given to the unemployed will be paid for at trade union rates.

That there will be no discrimination against the members of the unemployed organization.

That the city council call a special meeting tonight where the delegation of the unemployed will be present and decide what they will do about this.

The unemployed workers’ delegation was given an audience with City Council, but Hladun’s role, as a Communist, did not escape the notice of the local bourgeoisie. The Lethbridge manager of the Canadian Pacific Railway’s Colonization Department, O.T. Lathrop, personally accused Hladun of “causing trouble and disaffection among the men” and claimed between 40 and 50 men had arrived in town from Ontario over the previous few days. While other workers, including an Austrian and Hungarian, talked of hard times for anyone working farms, mines and railways, Hladun had to defend himself. While openly admitting his Communist affiliation, Hladun denied Lathrop’s claims of the crowd being “harangued” by “Communist propaganda.” Hladun said he was merely advocating to the crowd the necessity of organization in backing up the demand for work amidst capitalist decline.

The outcome of the City Council meeting was a resolution demanding the provincial government in Edmonton lean on the federal government in Ottawa to relieve the unemployment problem. The City Council had distributed $12,000 to the unemployed and would do no more without provincial or federal aid.

On the following Saturday, April 5, an unemployed demonstration of between 300 and 400 people paraded from Lethbridge’s Ukrainian Labour Temple to City Hall. Banners included the slogan “You brought us here, now support us”, “Full support or work at a union wage”, “We miners demand relief for unemployed” and “Down with the starvation government of capitalism”. A prominent speaker was James Sloan, president of the Lethbridge MWUC local. Sloan, who was not a Communist, was a miner who had been blacklisted by the United Mine Workers of America and had participated in the miners’ revolt that created MWUC in 1925.

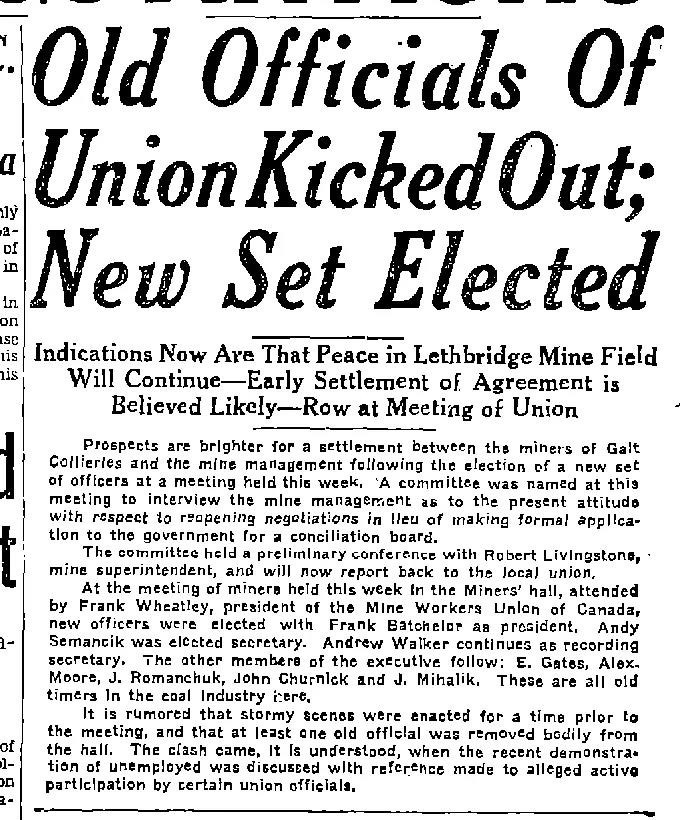

Meanwhile, Hladun, Murphy and their organization set the stage for the fight over the Lethbridge MWUC’s affiliation to the ACCL. However, this work proved contentious. According to Hladun, he and another influential Communist miner from the Crow’s Nest Pass, “Big John” Stolakiuk, opposed the speed with which Murphy moved to win the Lethbridge miners to the Workers’ Unity League. Unlike Murphy, Stolakiuk and Hladun were also members of ULFTA. Hladun says another party member whom he supported, possibly Stolakiuk, filed an appeal with party headquarters in Toronto to slow Murphy’s efforts. The appeal was overruled.

In his research on the MWUC, historian Allen Seager suggests there may have been a much deeper animosity between Murphy and Hladun because of Murphy’s view that the ULFTA was too conservative with regards to Communist Party priorities. Seager recounts Murphy clashing with Stokaliuk over strategy and tactics, and Stokaliuk regarding Murphy’s “dictatorial policy” as something that would discredit the Communist Party among coal miners.9

When it came to a mass meeting on the question of MWUC affiliation, Seager cites Hladun’s “They Taught Me Treason” account which he cautions as “probably overly cynical account of the Party’s activities there.”10 According to Hladun, the “judicious application of a few free beers” helped win over support for the local’s affiliation to the MWUC.

However, between Hladun’s account, Seager’s research, and reporting in the Lethbridge Herald, it is unclear what really happened at this meeting. The only major Lethbridge miners meeting reported by the Herald at this time was on April 22. In this meeting, the incumbent left-wing leadership, including James Sloan, was decisively defeated in a rowdy meeting. According to the Lethbridge Herald, Sloan and one other person was physically ejected from the meeting. More research is required.

The new executive set about negotiating a new deal with the coal operators, leading to conciliation over the summer. As for the Communist Party’s efforts with MWUC, the affiliation with WUL was largely won but not in Lethbridge at the time. Over the summer, a rank and file campaign was organized to recall Frank Wheatley, MWUC’s National President. This was achieved in a membership vote of 632 to 317, in which the Lethbridge local voted narrowly against recall. James Sloan was subsequently elected National President of MWUC.11

After the events of April 1930, Hladun’s work in Lethbridge is not known. Not too long after the MWUC meeting in Lethbridge, Hladun said he and Murphy were walking together on Calgary’s 8th Avenue when Murphy broke the news that the Communist from Ladywood was going to “Lenin University” in Moscow.

His journey to the Soviet Union had begun.

In the next installment of this series, we will follow Hladun’s journey through the Soviet Union and his subsequent role in the great political turmoil inside ULFTA and his departure from the Communist Party.

John Hladun, “They Taught Me Treason,” Macleans’ Magazine (October 1 1947); “They Taught Me Treason, Part II,” Macleans’ Magazine (October 15 1947); “They Taught Me Treason Part III,” Maclean’s Magazine (November 1 1947). The series was also published as They Taught Me Treason: The first-hand story of a Canadian farm boy trained by Moscow as a storm-trooper of a world-revolution (Maclean-Hunter Publishing, 1947).

Ivan Hladun, Inkoly ĭ odyn u poli voïn, (Hoverlia, 1990).

Vancouver Sun, April 12 1991.

Winnipeg Daily Tribune, December 1 1898.

Rhonda Hinther, Perogies and Politics: Canada’s Ukrainian left, 1891-1991 (University of Toronto Press, 2017), 87-91.

See Chapter One of Allen Seager’s dissertation, “A History of the Mine Workers’ Union of Canada 1925-1936,” MA Diss., McGill University (1977), p.16-53.

Ian Angus, Canadian Bolsheviks: The Early Years of the Communist Party of Canada (Trafford Publishing, 2006), 162-166.

Allen Seager, “Harvey Murphy,” The Canadian Encyclopedia, accessed April 8 2025.

Allen Seager, “A History of the Mine Workers’ Union of Canada 1925-1936,” MA Diss., McGill University (1977), p.93.

Seager, “A History of the Mine Workers’ Union of Canada 1925-1936,” p.92.

“Mine Workers’ Union Votes For Frank Wheatley’s Recall,” Edmonton Journal, June 18 1930; “Miners Elect New Officers,” Calgary Albertan, August 30 1930.