John Hladun's new pathway

Part one on the mercurial life of a Ukrainian-Canadian Anti-Communist

While researching the March 1945 red-baiting expulsion of Berry Richards and Dr. Johnson from the legislative caucus of the left-wing Cooperative Commonwealth Federation in Manitoba, I came across the name John Hladun in a statement by Richards and Johnson responding to their expulsion.

While arguing over the CCF’s foreign policy as part of their defence against charges of following Communist doctrine, Richards and Johnson called in their statement for the expulsion of John Hladun, a member of the Manitoba CCF’s Provincial Council; the very body that approved the expulsion of Richards and Johnson. The relevant passage in their statement read,

We produced literally dozens of quotations from C.C.F., in general, was weak in its policies on foreign affairs and, in particular, that it was anti-Soviet in its views. In order that the party leaders could prove their often-protested friendship for Russia, Mr. Richards introduced a resolution calling for the expulsion of John Hladun, a member of the provincial council, who wrote a strongly anti-Russian article in the Ukraine paper, “New Pathways.” The council promised to deal with the resolution on Sunday.

Winnipeg Free Press, March 12 1945

New Pathways was the Ukrainian-language paper of the Ukrainian National Federation, an organization based in Canada with allegiances to the Nazi collaborators of the Organization of Ukrainian Nationalists’ “Melnyk” faction. As late as November 1938, the UNF was touring Colonel Roman Sushko, the military commander of the OUN, while the OUN was being supported by German military intelligence, the Abwehr, as a terrorist group in Poland and Czechoslovakia. (Winnipeg Tribune, December 1 1938)

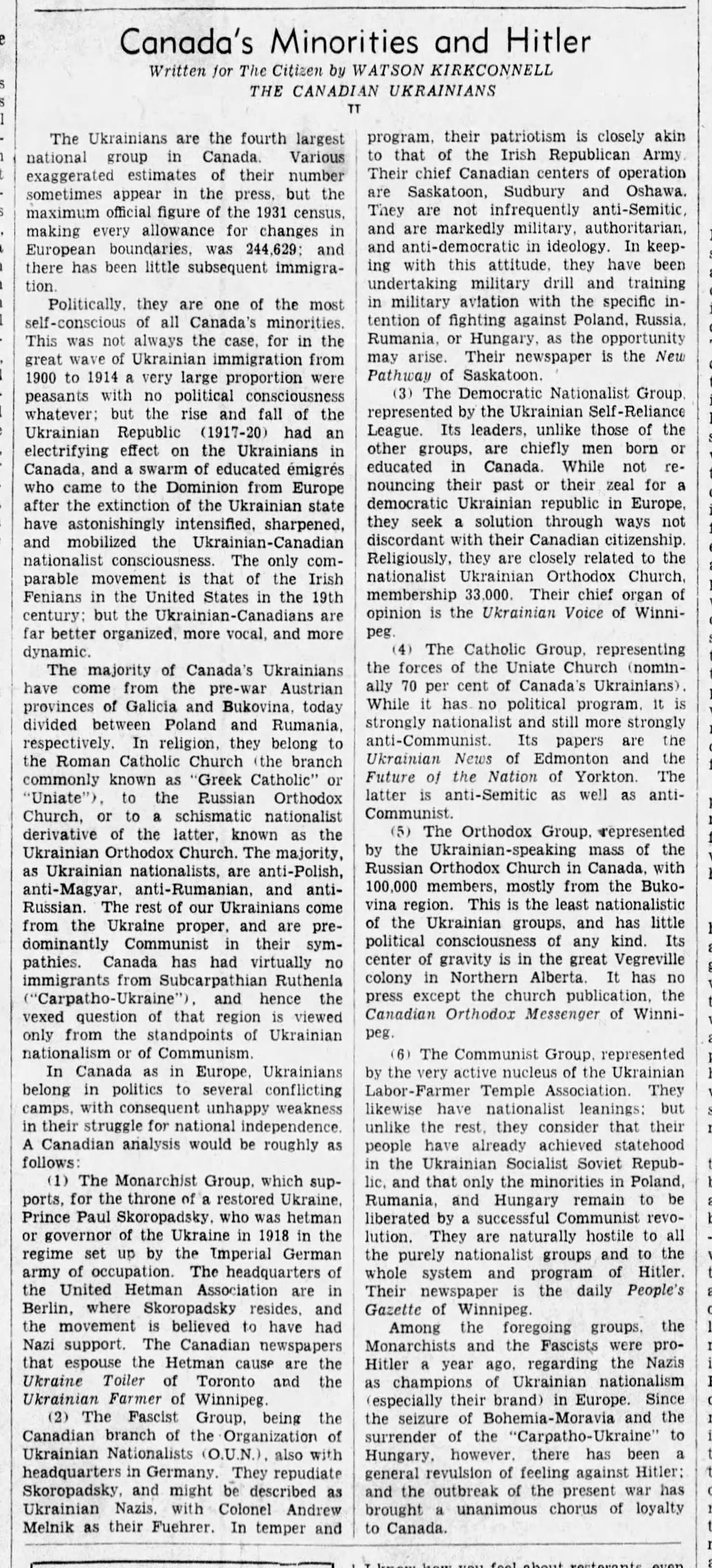

Unlike the suppression of the Communists in Canada at the outbreak of the Second World War, the UNF and other groups with open fascist sympathies were mildly suppressed or allowed to continue without interference. A case in point is the analysis promulgated by Watson Kirkconnell who was seen to be an expert on immigrant groups in Canada. In a widely-syndicated series of articles published early in the war entitled “Canada’s Minorities and Hitler”, Kirkconnell’s second article took a close look at “The Canadian Ukrainians” and described six political currents, including Monarchist, Fascist, Democratic Nationalist, Catholic, Orthodox, and Communist. On the Ukrainian fascists, Kirkconnell wrote,

The Fascist Group, being the Canadian branch of the Organization of Ukrainian Nationalists (O.U.N.), also with headquarters in [Berlin] Germany. They repudiate [German-based Monarchist leader] Skoropadsky, and might be described as Ukrainian Nazis, with Colonel Andrew Melnik [sp.] as their Fuehrer [sp.]. In temper and program, their patriotism is closely akin to that of the Irish Republican Army. Their chief Canadian centers of operation are Saskatoon, Sudbury and Oshawa. They are not infrequently anti-Semitic, and are markedly military, authoritarian, and anti-democratic in ideology. In keeping with this attitude, they have been undertaking military drill and training in military aviation with the specific intention of fighting against Poland, Russia, Rumania, or Hungary, as the opportunity may arise. Their newspaper is the New Pathway of Saskatoon.

Ottawa Citizen, October 5 1939

Kirkconnell continued by stating that “the Monarchists and the Fascists were pro-Hitler a year ago, regarding the Nazis as champions of Ukrainian nationalism (especially their brand) in Europe.” However, with the Nazi seizure of the Sudetenland (majority German-speaking regions) and dismemberment of Czechoslovakia in 1938, the Ukrainians were denied an independent state as the Nazis gave over southeast Czechoslovakia, or “Carpatho-Ukraine”, to Hungary. This, according to Kirkconnell, resulted in “general revulsion” and that the Monarchists and Fascists joined a “unanimous chorus of loyalty to Canada.”

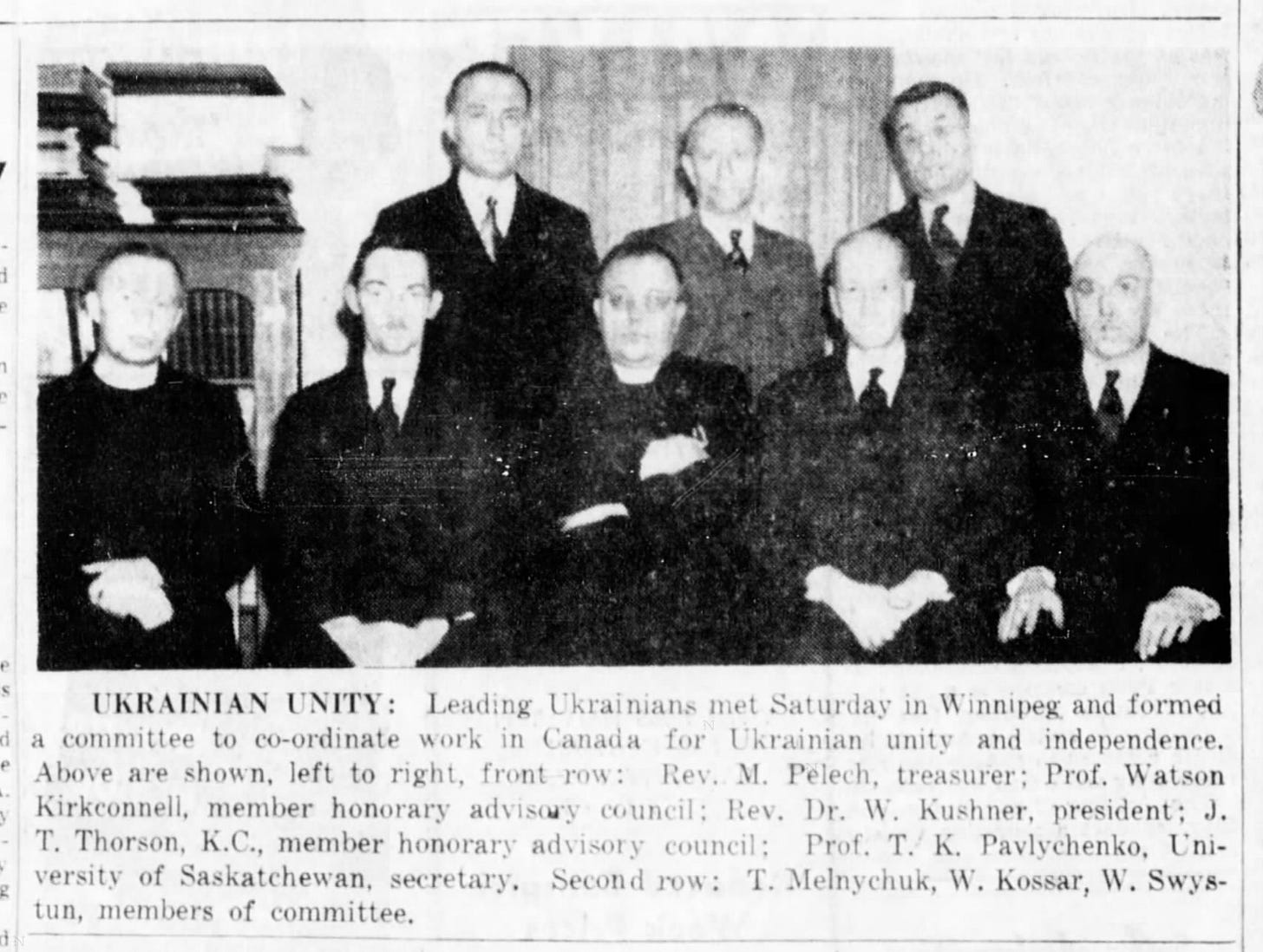

A year later, Kirkconnell was busy working with the Liberal Party of Canada and the Canadian federal government to form the Ukrainian Canadian Committee. The UCC was designed to unite all the aforementioned non-left Ukrainian currents against the Communist Party of Canada and in particular the much larger and influential Ukrainian Labor-Farmer Temple Association (ULFTA). Once the Communists were declared illegal by Canada’s federal government in 1940, much of the Communist-affiliated leadership of the ULFTA was arrested and jailed without charge, and its properties seized by the federal government. The properties were sold, often to the UCC’s member groups on the cheap.

The UNF was among the Ukrainian organizations that bought ULFTA properties and subsequently destroyed ULFTA records, furniture, art and other artifacts. The government-assisted takeover of ULFTA properties did not go unanswered. There were several clashes between right and left during the war, including at the ULFTA labour temples in Winnipeg and Toronto. The conflict between Ukrainian Communists and fascists had now spilled over into Canada, augmented by the federal government’s own anti-Communist intervention to create the UCC and declare the ULFTA an illegal organization. The UNF, however, was never declared illegal despite its open alliance with the Nazi-supported OUN.

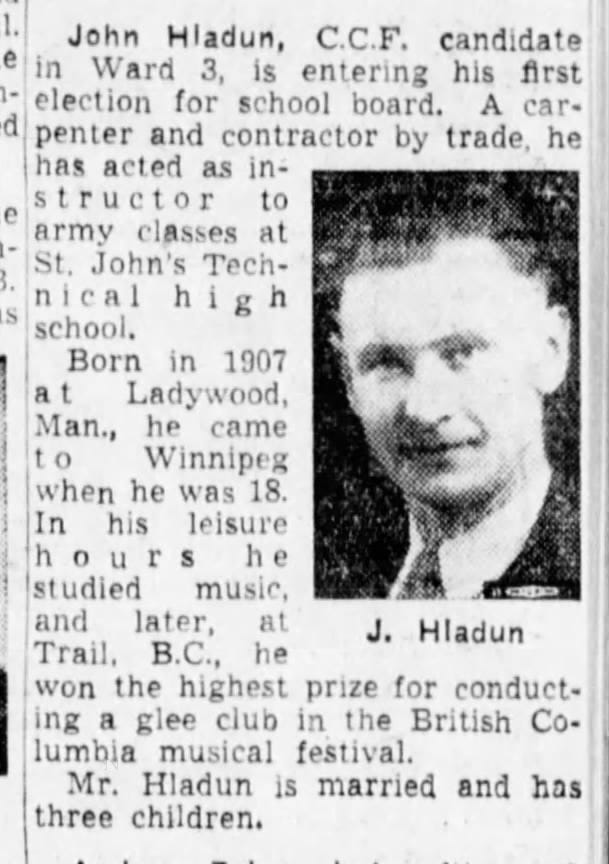

Hladun’s 1943 school board run

At the time of these clashes, Hladun was living at 96 Eaton Street in the working-class Winnipeg suburb of Elmwood, a short distance from the banks of the Red River opposite Point Douglas. Hladun was a carpenter and contractor and also had a job instructing army classes on carpentry in the basement floor of St. John’s Technical, an impressive three-story high school built of Tyndall Stone and located on Machray Avenue. Built between 1910 and 1912, the school was demolished in 1967 and replaced with a new facility of the same name.

While further research is required to establish when Hladun was first elected to the Provincial Council, we know he was nominated to be a CCF Ward 3 school board candidate in early October, 1943. It was still the era of multi-member wards, and Winnipeg’s Ward 3 had three seats available in a run-off single-transfer vote. For voters, this meant ranking candidates on the ballot. Once a candidate reached the threshold to be elected, their remaining votes were transfered while the candidate with the lowest votes was eliminated. Additional rounds of votes would be tabulated until three candidates met the threshold to be elected.

The two other CCF candidates were Meyer Averbach and Jack Peden. Averbach was a lawyer and principal of Winnipeg’s Talmud Torah school, or Hebrew Free School, and a prominent member of the Canadian Jewish Congress. Averbach had a history of supporting labour candidates, notably A.A. Heaps’ successful 1935 re-election to parliament in Winnipeg North in which Liberal and Conservative challengers waged anti-Semitic attacks on Heaps and his many Jewish supporters. Peden was a student at the University of Manitoba studying to become a civil engineer.

The municipal vote was held November 26, and Hladun finished last out of the eight candidates in Ward 3. Averbach came second. Coming third was Joseph Zuken of the Communist Party, running under a legal “Labour” banner. Narrowly topping the list was Andrew Zaharichuk, a candidate of the right-wing Civic Election committee. Zaharichuk was also involved in the new Ukrainian Canadian Committee.

Hladun’s 1944 run for City Hall

The day after Canadian troops landed on the beaches of Normandy on June 6, 1944, the CCF’s North Winnipeg Constituency Association met to elect new officers at the party’s clubhouse at 1170 Main, a short 15 minute walk from St. John’s Technical. Seven new officers were elected, including John Hladun as secretary.

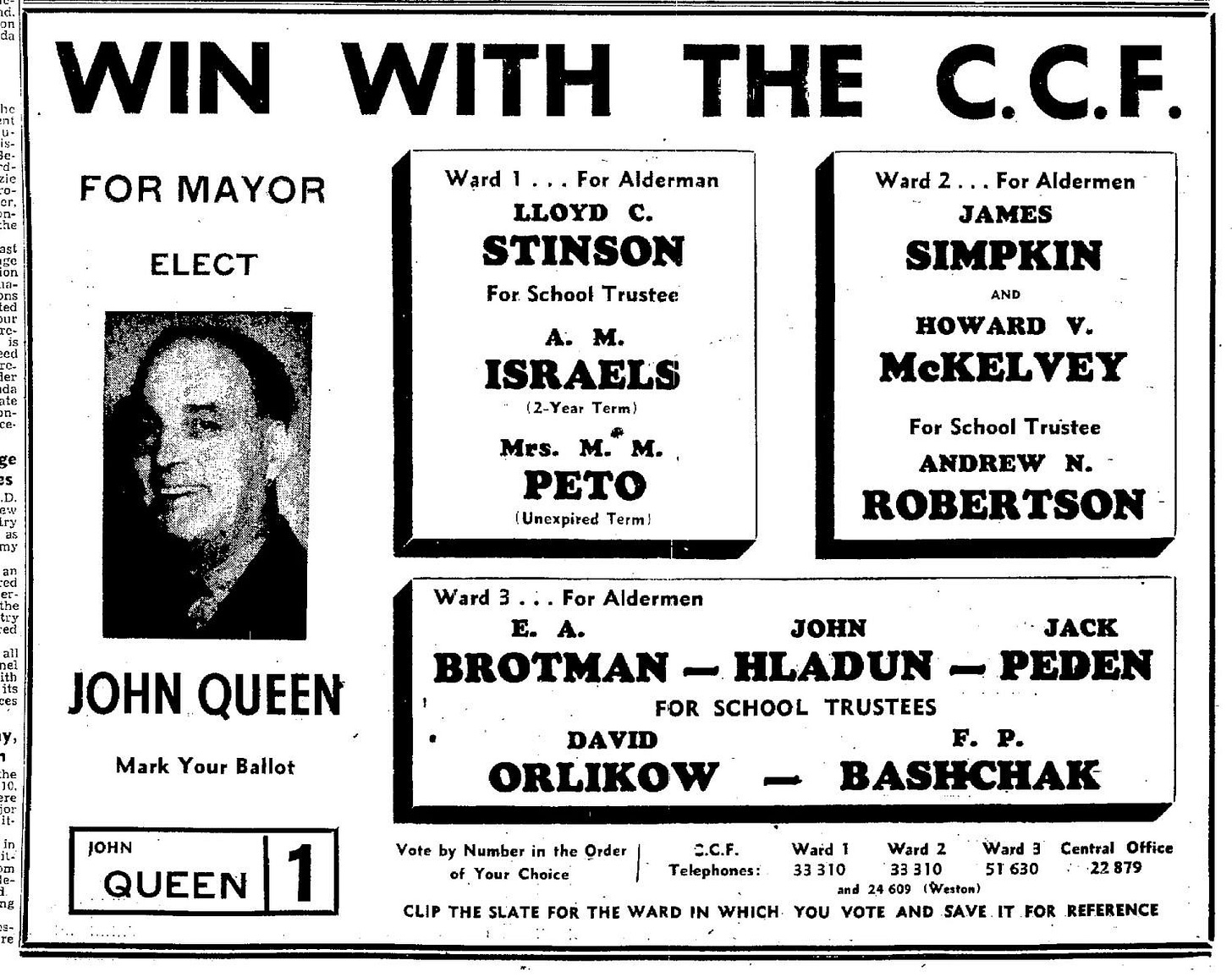

A few months later, on September 28 at the Marlborough Hotel in downtown Winnipeg, Hladun was among a slate of CCF aldermanic and school board candidates nominated in a city-wide CCF convention. Hladun would run again in Ward 3 but this time as an aldermanic candidate alongside two other CCF candidates, Jack Peden and Ernest A. Brotman. Brotman, a lawyer, had been elected for the first time to City Hall the year earlier when Hladun ran for the school board.

In between the 1943 and 1944 elections, Hladun moved to 67 Noble Avenue, also a small house, located in Glenelm and a very short distance to the Redwood Bridge (now Lazarenko Bridge). The bridge allowed Hladun a much shorter route to St. John’s Technical and the CCF clubhouse off Main Street.

During his 1944 campaign, Hladun spoke over CKRC’s airwaves on the evening of November 16, just a few days from the election. On November 22, the CCF held a Ward 3 election meeting at Averbach’s Hebrew Free School located at the intersection of Charles and Flora. It was reportedly sponsored by the local Labor-Zionist movement. The keynote speaker was John Queen, the CCF’s mayoral candidate, as well as Hladun, Peden, Brotman and school board candidates Dave Orlikow and F.P. Baschak. (Winnipeg Free Press, November 23 1944)

The election was held Friday, November 24. In Ward 3, the popular local Communist, Jacob Penner, was elected after recently being released from jail after being held without charge since the 1940 suppression of the Communist Party. Alongside Penner, local businessman and politician, Wasyl Scraba, was elected for the CEC. Brotman also won re-election for the CCF.

Hladun ranked sixth of eight candidates, ahead of a CEC and a PEC (Communist) candidate. Out of 20,101 first votes, Hladun came sixth and only collected 833. Penner and Scraba were elected on the first ballot, and once transfers were counted, Brotman was elected third, with Hladun only securing another 279 transferred votes. Of those 279 transferred votes to Hladun, 184 came from the right-wing Scraba, and only 15 from known Communist, Jacob Penner. (Winnipeg Free Press, November 28 1944)

Out of the CCF and on to Toronto

We know Hladun was a member of the CCF Provincial Council on March 10 1945 when it voted 33-5 to suspend their popular provincial organizer and The Pas MLA, Berry Richards, and Brandon MLA, Dr. Johnson. (Winnipeg Free Press, March 12 1945)

Richards and Johnson made a point in their subsequent statement, cited at the start of this article, of calling for the expulsion of Hladun for his anti-Soviet views being published in the UNF newspaper, New Pathway. There are no newspaper reports confirming the Provincial Council expelled Hladun or even met on March 11.

As late as August 1945, Hladun was still in Winnipeg. Hladun was reported to be the contractor for the Manitoba Vegetable and Potato Growers’ Co-operative Association’s new cold storage and warehouse facility at the corner of Sutherland and Derby beside the CPR yard just west of Point Douglas. (Winnipeg Tribune, August 31 1945)

Hladun would later confirm his departure from the CCF in 1945, but his explanations were completely contradictory. In a 1949 court case, to be examined in a later installment of this series, Hladun testified under oath that he had not been expelled from the CCF in 1945 (Toronto Star, December 6 1949). However, he also claimed at a public meeting earlier that same year that he “was kicked out of that party for being too anti-Communist.” (St. Catharines Standard, January 26 1949)

Hladun resurfaced in 1947 in Toronto. On August 16 1947, the Globe & Mail reported on a letter sent my Hladun to the Soviet Embassy in Ottawa alleging a Soviet embassy employee, I.O. Scherbatiuk, had described at a public event in Winnipeg that Ukraine’s Displaced Peoples were “liars and dishonest persons”. According to the Globe & Mail report, Scherbatiuk’s claim was made at a Ukrainian picnic and subsequently published in the Winnipeg-based Ukrainian Word, newspaper of ULFTA’s successor, the Association of United Ukrainian Canadians. The controversy stemmed from the efforts of the UCC to bring Ukrainian refugees to Canada whom many, especially the Communists, understood to be fascists and Nazi collaborators.

Based on research to date, it is unclear if Hladun’s letter initiated an inquiry by the federal government’s External Affairs Department into Scherbatiuk remarks at the picnic in St. Vital, Winnipeg, on July 27. A few months later, in early November, Ottawa issued an official warning to the Soviet Union saying they would recall any foreign diplomats breaching diplomatic protocls, adding that, if accurate, Scherbatiuk’s comments were “clearly offensive” and “calculated to promote ill-will and hostility between different groups of people in Canada.” (Montreal Gazette, November 7 1947)

Hladun, it seemed, had begun to transform himself into an influential man of letters. Not long after his August letter to the Soviet Embassy, Hladun wrote a letter to the Windsor Star in September and then the Globe & Mail again in October 9. Both letters defended Watson Kirkconnell’s selection as a speaker at “United Nations Week” in Windsor, which had caused controversy, especially among those who had sympathies with the Soviet Union and opposed the Canadian government suppression of the Communist Party and broader left.

Kirkconnell’s role in the formation of Ukrainian Canadian Committee in 1940, his anti-Communist lectures during the war, and wartime anti-Communist pamphlets, had led Kirkconnell to become a target of criticism for Communists in Canada and even the Soviet Union. Kirkconnell was portrayed as a fascist, even a “fuhrer” for Ukrainian fascists coming to Canada. As Gordon L. Heath has documented, Kirkconnell was in fact collaborating directly with the RCMP in a covert anti-Communist witchhunt targeting, according to Heath, “professors, politicians, publishers, and even students.” Kirkconnell, meanwhile, continued his collaboration through the 1940s with fascist Ukrainian organizations and individuals he deemed to be reformed.

Describing Kirkconnell as an “annihilating critic of communism and other totalitarianisms,” Hladun’s October letter in the Globe was afforded plenty of space to elaborate on Communist “infiltration methods”, party organization, information gathering, and how Communists take control of unions.

This line of attack, published on October 9, was now the bread and butter of John Hladun’s “tell-all” allegations against the Communist Party of Canada which would transform him into one of Canada’s most prominent anti-Communist speakers in the late 1940s. The first part of his “They Taught Me Treason” series in Macleans’ Magazine had been published a little over a week earlier.

Next in the John Hladun series…

We will examine Hladun’s account of his time in the Communist Party of Canada between 1928 and 1933, recounted in Macleans’ Magazine over October and November 1947, and reconstruct what we know about Hladun’s life before he ran for public office in 1943.